Introduction to Exploit Development & x86 Architecture

Hello and welcome to the first blog in my Windows user-mode exploit development series! If you're reading this, it means you're interested in Windows binary exploitation. In this series, I’ll take you from zero to hero, covering everything from beginner-friendly fundamentals to advanced techniques for x86 exploitation.

The series is structured into four parts, with this first one designed to build a strong foundation by introducing x86 architecture, the importance of exploit development, and why it’s such a crucial skill today. We’ll wrap up this part by crafting our very first vanilla buffer overflow exploit.

As of now, only Series 1 is published, but rest assured, the remaining three will follow—potentially even more, depending on my research. Stay tuned!

Before diving into this series, get your Windows x86 VM ready along with Kali and enjoy the ride :3

Why Exploit Development Matters

Exploit development remains a critical skill in cybersecurity. Despite years of advancements in mitigations and security mechanisms, new binary exploits continue to emerge, proving that no system is completely secure. Understanding how vulnerabilities are exploited allows security researchers, penetration testers, and even defenders to build more effective protections and develop countermeasures against real-world threats.

In this series, we will be focusing on x86 exploitation. The reason for this is simple: learning exploitation from scratch is significantly easier on x86 than on x64. The x86 architecture has simpler calling conventions, fewer registers, and more well-documented legacy exploits, making it an ideal starting point. Once you grasp the fundamentals of memory corruption, stack overflows, and shellcoding in x86, transitioning to x64 becomes much easier, as the core principles remain the same with only structural changes.

Mastering exploit development isn’t just about breaking things—it’s about understanding how modern security works, bypassing protections like DEP, ASLR, and stack canaries (which we’ll cover in upcoming series), and ultimately thinking like an attacker to strengthen overall security. Whether you're aiming for offensive security, vulnerability research, or bug bounty hunting, these skills are essential in today’s cybersecurity landscape.

Program Memory & Stack Fundamentals

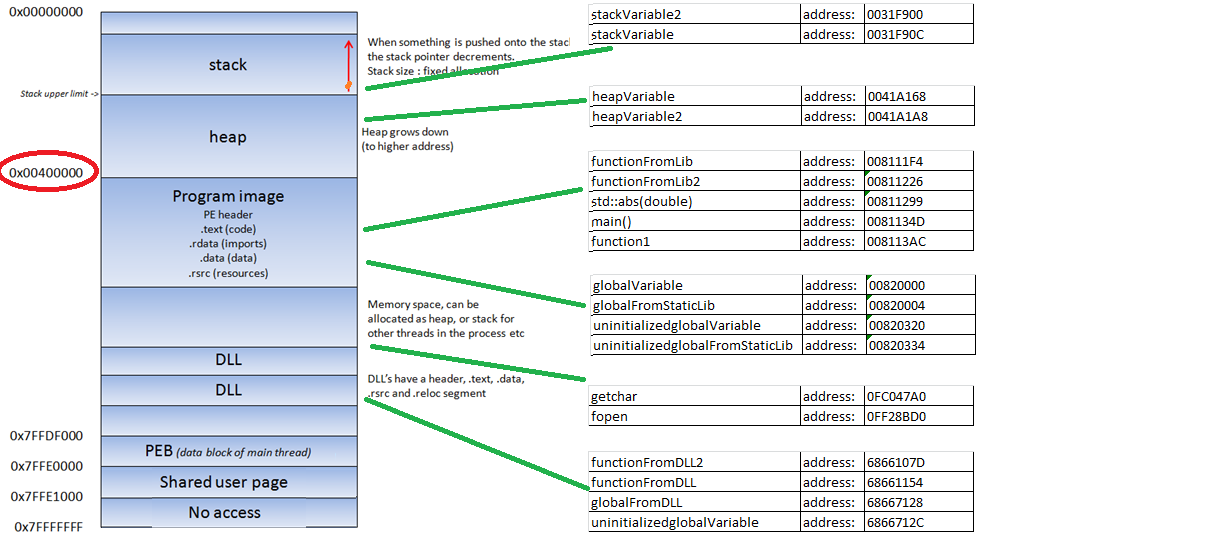

Before diving into debugging, memory corruption, or writing exploits, we need to understand program memory at the CPU level and familiarize ourselves with some basic definitions.

While there are several key memory areas in a program, for the purpose of this series, we’ll focus mainly on the stack. We won’t go into a deep dive, but you can refer to other resources for more detailed information if needed. Let's start with the basics:

The Stack

The stack is a special area of memory used for short-term data storage, specifically for function calls, local variables, and control information. When a thread is running and executing code from the program or DLLs, data is pushed to the stack to keep track of the function calls and their variables. The stack operates on a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) principle, meaning that the most recently added data is the first to be removed.

- PUSH: Places an item on the stack.

- POP: Removes the top item from the stack.

This structure is essential to understand when dealing with buffer overflows, as you’ll manipulate values on the stack to control the program’s flow.

Calling Conventions

A calling convention defines the low-level mechanism by which functions receive parameters from their caller and how they return values. It determines how arguments are passed, either through CPU registers or by being pushed onto the stack.

- The compiler typically decides which calling convention to use, but it can be overridden by programmers for specific functions if necessary.

- Calling conventions affect function performance and compatibility, and it’s crucial to understand them when working with exploitation techniques, especially in relation to buffer overflows and shellcoding.

Function Return Mechanics

When a function is called, it executes and then needs to return to the place it was originally called from. To achieve this, the program uses a special piece of data: the return address. This address points to the instruction right after the function call, where the program should resume execution once the function finishes.

- Stack Frame: When a function is called, the return address and any function parameters are pushed onto the stack. This forms what is known as the stack frame for that function.

- Return Flow: When the function ends, the return address is popped off the stack, and the program execution jumps to that address, resuming where it left off.

This mechanism is critical in exploit development, as it enables us to control the program's execution flow, particularly through stack overflows.

CPU x86

To execute code, the CPU in the x86 architecture utilizes 32-bit registers. These registers are small, extremely fast storage locations within the CPU, designed to store and manipulate data efficiently.

General Purpose Registers

There are several general-purpose registers in x86, such as EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX, ESI, and EDI. These registers store temporary data, which can be used for various purposes during program execution. While there is much more to this topic (detailed in various online resources, refer to this), the main registers that we'll focus on are as follows:

- EAX (Accumulator): Used for arithmetic and logical operations.

- EBX (Base): Serves as a base pointer for memory addressing.

- ECX (Counter): Commonly used for loop counters and shift/rotate operations.

- EDX (Data): Used for I/O port addressing and multiplication/division operations.

- ESI (Source Index): Points to the source data in string operations (e.g., string copying).

- EDI (Destination Index): Points to the destination data in string operations.

ESP - The Stack Pointer

As previously mentioned, the stack is used for storing data, pointers, and function arguments. Since the stack is dynamic and constantly changing during program execution, the ESP (Stack Pointer) register keeps track of the most recent location in the stack, effectively pointing to the top of the stack.

EBP - The Base Pointer

Given that the stack evolves during execution, it can be challenging for a function to locate its stack frame, which contains critical information such as the function's arguments, local variables, and return address. The EBP (Base Pointer) resolves this issue by holding a pointer to the start of the stack frame when a function is called. By referencing EBP, a function can easily access its stack frame data using specific offsets.

EIP - The Instruction Pointer

The EIP (Instruction Pointer) is one of the most critical registers when dealing with exploitation. It always holds the address of the next instruction to be executed in the program. Since EIP dictates the program’s flow, it becomes a primary target for attackers exploiting memory corruption vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows. By manipulating the EIP, attackers can alter the execution flow of the program and redirect it to malicious code.

Now that we built a basic foundation on x86 architecture, we can start diving into exploiting a basic memory corruption vulnerability, often labeled as vanilla buffer overflow. But before that, let’s explore our main debugger which we are going to work with: WinDbg. That’s the topic for the next blog. See you there!